An aortic aneurysm is a bulge in the wall of your aorta, the main artery from your heart. Aortic aneurysms form in a weak area in your artery wall. They may rupture (burst) or split (dissect), which can cause life-threatening internal bleeding or block the flow of blood from your heart to various organs.

What is an aortic aneurysm?

Your aorta is the largest artery in your body. It carries blood and oxygen from your heart to other parts of your body. It’s shaped like a curved candy cane. Your ascending aorta leads up from your heart. Your descending aorta travels back down into your abdomen (belly).

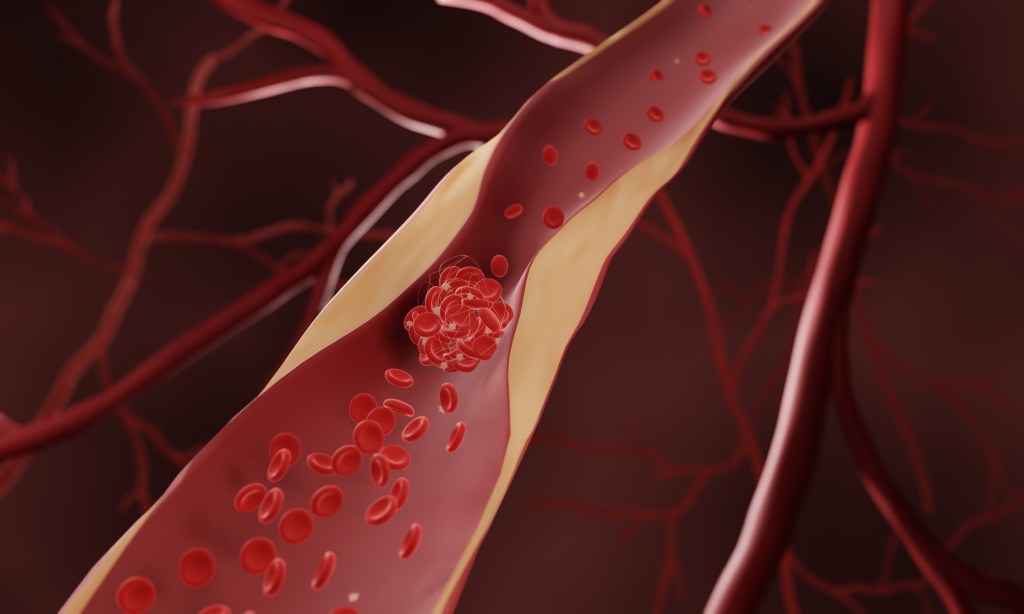

An aneurysm can develop in any artery. An aortic aneurysm develops when there’s a weakness in the wall of your aorta. The pressure of blood pumping through the artery causes a balloon-like bulge in the weak area of your aorta. This bulge is called an aortic aneurysm.

What are the different types?

There are two different types of aortic aneurysms. They affect different parts of your body:

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA): An abdominal aortic aneurysm develops in the “handle” of your aorta that points down.

- Thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA): A thoracic aortic aneurysm (heart aneurysm) occurs in the section that’s shaped like an upside-down U at the top of your aorta. In people with Marfan syndrome (a connective tissue disorder), a TAA may occur in the ascending aorta.

How common are they?

Abdominal aortic aneurysms are 4 to 6 times more common in men and people assigned male at birth than women and people assigned female at birth. They affect only about 1% of men aged 55 to 64. They become more common with every decade of age. The likelihood increases by up to 4% every 10 years of life.

Abdominal aortic aneurysms occur more frequently than thoracic aortic aneurysms. This may be because the wall of your thoracic aorta is thicker and stronger than the wall of your abdominal aorta.

What are the risk factors for aortic aneurysm?

Both your family history and your lifestyle can play a role in your risk of developing an aortic aneurysm. Aortic aneurysms occur most often in people who:

- Smoke.

- Are over age 65.

- Were assigned male at birth.

- Have a family history of aortic aneurysms.

- Have high blood pressure (hypertension).

What causes aortic aneurysm?

The causes of an aortic aneurysm are often unknown, but can include:

- Atherosclerosis (narrowing of the arteries).

- Inflammation of the arteries.

- Inherited conditions, especially those that affect connective tissue (such as Marfan syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome).

- Injury to an aorta.

- Infections, such as syphilis.

What are the symptoms of an aortic aneurysm?

In many cases, people don’t know they have an aortic aneurysm. An aneurysm often doesn’t cause any symptoms until it ruptures (bursts).

If an aneurysm ruptures, it’s a medical emergency that requires immediate treatment. Call 911 if you or someone you are with has a ruptured aneurysm.

Symptoms of a ruptured aneurysm come on suddenly and can include:

- Dizziness or lightheadedness.

- Rapid heart rate.

- Sudden, severe chest pain, abdominal pain or back pain.

Finding an aortic aneurysm before it ruptures offers your best chance of recovery. As an aortic aneurysm grows, you might notice symptoms including:

- Difficulty breathing or shortness of breath.

- Feeling full even after a small meal.

- Pain wherever the aneurysm is growing (could be in your neck, back, chest or abdomen).

- Painful or difficult swallowing.

- Swelling of your arms, neck or face.

What are the complications of an aortic aneurysm?

If an aortic aneurysm ruptures, it causes internal bleeding. Depending on the location of the aneurysm, a rupture can be very dangerous — even life-threatening. With immediate treatment, many people can recover from a ruptured aneurysm.

A growing aortic aneurysm can also lead to a tear (aortic dissection) in your artery wall. A dissection allows blood to leak in between the walls of your artery. This causes a narrowing of your artery. The narrowed artery reduces or blocks blood flow from your heart to other areas. The pressure of blood building up in your artery walls can also cause the aneurysm to rupture.

How is aortic aneurysm diagnosed?

Many aneurysms develop without causing symptoms. Providers often discover these aneurysms during a routine checkup or screening.

If you’re at high risk of developing an aortic aneurysm — or have any aneurysm symptoms — your provider will do imaging tests. Imaging tests that can find and help diagnose an aortic aneurysm include:

- CT scan.

- CT or MRI angiography.

- Ultrasound.

How is an unruptured aortic aneurysm treated?

If you have an unruptured aortic aneurysm, your provider will monitor your condition closely. If you have risk factors for developing an aortic aneurysm, your provider may also recommend regular screenings.

Treatment aims to prevent the aneurysm from growing large enough to tear the artery or burst. For smaller, unruptured aneurysms, your provider may prescribe medications to improve blood flow, lower blood pressure or manage cholesterol. All can help slow aneurysm growth and reduce pressure on the artery wall.

What are the types of aortic aneurysm surgery?

Large aneurysms at risk of dissecting or rupturing may require surgery. Your provider might use one of these types of surgical procedures to treat an aortic aneurysm:

- Open aneurysm repair: Your provider removes the aneurysm and sews a graft (a section of specialized tubing) in place to repair the artery. Open aneurysm repair surgery may also be necessary if an aneurysm bursts.

- Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR): Endovascular surgery is a minimally invasive procedure to fix aortic aneurysms. During the procedure, your provider uses a catheter (thin tube) to insert a graft to reinforce or repair the artery. This procedure is also called thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair (TEVAR) or fenestrated endovascular aneurysm repair (FEVAR).

What can I expect after aortic aneurysm surgery?

Recovery after aneurysm surgery takes a month or longer. Your provider will continue to monitor you for changes to the aneurysm, growth or complications. Most people have positive outcomes after surgery.

All surgery has risks. Possible complications after surgery include:

- Leaking blood around the graft (called endoleak).

- Movement of the graft away from where it was placed.

- Formation of blood clots.

- Infection.

Can I prevent an aortic aneurysm?

Having high blood pressure, high cholesterol or using tobacco products increases your risk of developing an aortic aneurysm. You can reduce your risk by maintaining a healthy lifestyle. This includes:

- Eating a heart-healthy diet.

- Getting regular exercise.

- Maintaining a healthy weight.

- Quitting smoking and using tobacco products.

What is the prognosis (outlook) for people with an aortic aneurysm?

With careful monitoring and treatment, your provider can help you manage an aortic aneurysm. Ideally, your healthcare team can identify and care for an aortic aneurysm before it ruptures.

If an aortic aneurysm ruptures, seek medical care immediately. Without prompt treatment, a ruptured aortic aneurysm can be fatal. Both open and endovascular surgery can successfully treat a ruptured aortic aneurysm.

When should I call the doctor?

You should call your healthcare provider if you experience:

- Loss of consciousness (syncope, fainting or passing out).

- Low blood pressure.

- Rapid heart rate.

- Sudden, severe pain in your chest, abdomen or back.

What questions should I ask my doctor?

You may want to ask your healthcare provider:

- Am I at risk of developing an aortic aneurysm?

- How will I know if I have an aortic aneurysm?

- What steps can I take to prevent an aortic aneurysm from dissecting or rupturing?

- What lifestyle changes will help reduce my risk of an aortic aneurysm?

A note from QBan Health Care Services

Taking steps to improve your heart health can help prevent aortic aneurysms from developing or getting worse. Talk to your doctor about lifestyle changes you can make. If you’re at risk for an aortic aneurysm, be sure to get regular screenings. Finding and treating an aneurysm early greatly reduces the risk of rupture or other complications.